The Future of Conflict in an Age of Climate Extremes

By the GGF 2035 Global Futures of Climate-Related Conflict Working Group

The working group on the futures of climate-related conflict considers climate change a major environmental threat. It is also likely to have a seismic impact on human security, access to resources and (violent and non-violent) conflicts. Climate change will create new challenges and dramatically exacerbate existing ones, including through increased pressure on land use, a diminishing availability of drinking water and damage to coastal areas. These challenges will affect the distribution of key resources and communal living within as well as across the confines of national borders. As such, climate change has the potential to become both a risk multiplier and direct cause of conflict.

We identified four key trends that pervade both of our scenarios for the years 2035: 1) decreasing volumes of drinking water for large parts of the world; 2) the growing political and economic power of China; 3) increasing urbanization across high- and middle-income economies; and 4) (violent and non-violent) conflict, contestation and cooperation between states. The use of technology, including (broadly understood) geo-engineering technology and, in particular, local and regional weather modification technology, is relevant for both our scenarios. While we understand geo-engineering as “the deliberate, large-scale manipulation of the planetary environment to counteract anthropogenic climate change,” our analyses focus primarily on weather modification technology and some “nature-based” solutions at the local and regional levels.

Table 1: Key Uncertainties and Respective Projections for a

Pleasant (Green) and Unpleasant (Red) Future of Climate-Related Conflict

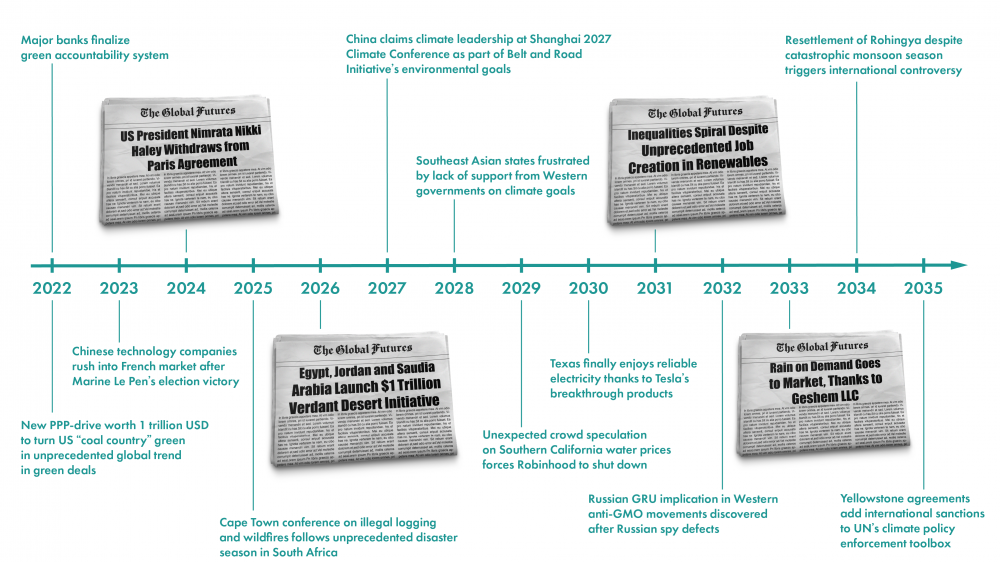

Scenario I (“Climate Disorder Under Orders”) examines how three primary dynamics will evolve into 2035. First, local politics will increasingly influence national and global politics. Second, technology will occupy a significant role in countering the negative impacts of climate change and, at the same time, pose new challenges and risks to conflict mitigation. Third, traditional alliances will fracture and wither, creating space for new forms of cooperation (including public-private partnerships) and alliances between countries to emerge. While these three dynamics occur simultaneously and influence one another, they are presented separately so as to emphasize each one’s key drivers. This scenario explores how the highly disruptive consequences of climate change could: affect the availability of natural resources; impact global financial markets; increase international investment in geo-engineering and, in particular, weather system technologies; reshape the contours of conflict between nation states; and lead to a reimagining of the future of climate-related migration.

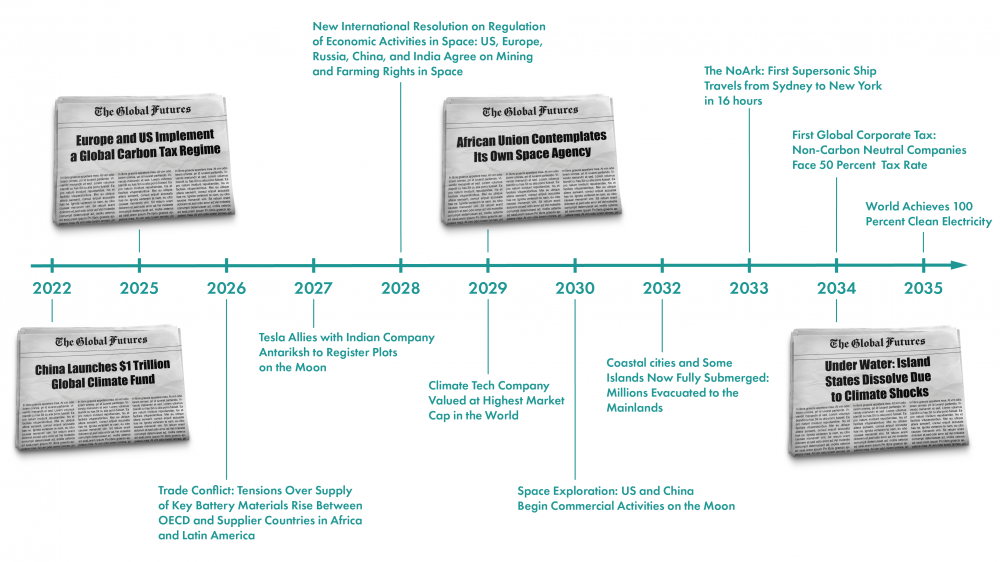

In Scenario II (“Building the Great Green Wall”), international cooperation results in more effective global governance on climate policy, which is the key driver within the multi-polar world emerging through 2035. This new global order is shaped by newly forming regional blocs, which permit access to scarce natural resources, capital, military power, and technologies. These blocs are led by regional superpowers (India, China, the EU, the US, etc.) that negotiate on behalf of their member states. Most conflicts between these competing blocs ignite around the issue of access to resources needed for machine-driven innovations for food production, the energy transition toward 100 percent renewable energy, and the green mobility transition. Consumption and production growth drive scarcity of critical resources, such as rare earth materials, fertile agricultural land and access to freshwater. International migration remains a contested issue. While climate-related migration is well managed nationally (as part of larger national climate adaptation frameworks), the international community continues to fail cross-border migrants fleeing war, violence and extreme poverty.

Snapshot of Scenario I

In 2035, all three dynamics that drive this scenario (local conflict, technological advancements and global political disjunction) are at play, with local and national politics acting as first among equals. Humanity is struggling with the effects of numerous intense climate events. So-called Climate Clubs – countries with the same climate objectives – are created to enhance collaboration on technologies and policies to address climate-related challenges. This results in regional polarization, with the US and China as the two main leaders in a multipolar world. While weather modification technology exists, only certain countries, citizens and corporations enjoy access to it, and the effectiveness of these technologies in mitigating the negative impacts of climate change is disputed.

Erratic climate events precipitate skyrocketing profits for futures pricing, thus benefiting investors and the upper echelon of societies.

New food technologies, such as 3-D printed foods, are available only to the very rich, while scalable technologies, such as genetically modified (GM) seeds, face serious push-back from farmers in emerging economies. The spread of mis- and disinformation regarding GM food technology (such as that these foods cause health issues and impotency) exacerbates resistance to GM technology, leading to food shortages in countries like India and Nigeria and destabilizing regional competitors. Erratic climate events precipitate skyrocketing profits for futures pricing, thus benefiting investors and the upper echelon of societies. Meanwhile, high volatility in global resource management (reflected, for instance, in the short cycles with which global extraction companies open and close their regional offices) exerts even more pressure on those already buckling at the bottom of different national economies.

Regional and global politics are also affected by these developments. Closer partnerships blossom between countries with similar climate objectives (e.g., between the US and Japan), while traditional alliances (such as between the US and the EU) wither. This creates new opportunities for collaboration and partnerships in other areas, such as collaboration between China and the EU in the realm of smart grids. Specialized or highly skilled workers are gravitating toward spaces where economic opportunity is high, thus forsaking areas subject to economic stagnation due to the adverse effects of increasingly frequent climate shocks.

What Are the Main Factors Driving this Scenario?

All Politics Are Local

For governments across the world, domestic and global political decision-making are influenced by developments in the US-China relationship and perceptions of China’s advancements in green technology. Governments feel pressured to choose between backing the US or the China ‘camp’. Domestic politics intersect with geopolitics, causing significant polarization around regional investments in, agreement with and distribution of effective technological as well as non-tech solutions to climate change. This generates economic and political pressures globally.

- US-China relations: Because of US political vacillation and bi-partisan hostility toward China, Beijing alienates the US and sides with the increasingly fractured EU on climate policies as well as technological cooperation. Many Southeast Asian countries’ climate policies emulate China’s strategy, the result of Beijing’s successful COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy and lessening tensions in the South China Sea.

- Privatization of common public goods: Privatization of common goods (such as water) will fuel inequities in access to natural resources.

- Domestic climate-related migration: Highly specialized economic migrants leave areas that are subject to economic stagnation due to the adverse effects of increasingly frequent climate shocks. Major cities become areas of concentration for people with privilege and talent, leading to over-saturation. At the same time, around the world, areas vulnerable to climate change become increasingly abandoned and dilapidated.

No Deus Ex Machina

There is an overall push in the search for technological solutions to counter the negative impacts of climate change. This invites unprecedented investment in weather system intervention technologies (locally as well as regionally), which, in turn, spurs corporate espionage. Technology mitigates some climate shocks; however, it also intensifies challenges in the realm of conflict mitigation, as irregular and inconsistent access to technology breeds conflict internationally and locally.

- Water scarcity: Water scarcity continues to threaten countries around the globe. As a result, technologies like seawater desalination and weather manipulation (through atmospheric water capture, precipitation and more) are deployed at a growing scale. Issues like waste dumping and resource grabbing intensify within and across world regions (especially in the Global South, where land property rights are weak).

- AgTechs: The efficiency of agriculture improves, a development that is driven by innovative AgTechs (which include technologies like precision robotics and the use of space data for agriculture). However, global needs persist as the world’s population continues to expand. Moreover, growing resistance to GM seeds (a function of health concerns and misinformation) leads to global food shortages.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

Traditional alliances fracture and wither, making space for new constellations of collaboration between countries and public-private sector partnerships in various jurisdictions. Some countries foster their alliances at the expense of regional polarization.

- New partnerships: The fracturing of traditional alliances creates new pressures for innovation and business coordination.

- Carbon tax and loans: Global financial markets begin to mandate carbon taxes, and relevant actors factor the costs of environmental and climate change impacts into their decision-making about loans.

Scenario I: Climate Disorder Under Orders

All Politics Are Local

By 2035, many parts of the world will have suffered from devastating climate disasters. In the past 15 years, the world has experienced a ten-fold increase in the number of typhoons, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires. This has led to crop shortages, water insecurity and high infrastructure costs worldwide. This period has also seen soaring investments in technology, futures of natural resources and commercial space exploration (such as in the low Earth orbit by actors like Starlink or OneWeb). A global scrambling for access to natural resources and rare earth materials, along with a decade and a half of EU-China climate competition, has divided the world into vying blocs: one led by the US, one led by China and a third group of states fighting for their very survival. In an effort to take matters into its own hands, the US backs the Yellowstone Agreement, which comes into effect in 2035. This agreement establishes the North American Climate Goals, as the Paris Agreement flounders. The same year, several Southeast Asian countries join the Thimphu Agreement, thus setting new clean water goals to protect freshwater resources in a region already plagued by water shortages.

By 2035, the world has experienced a ten-fold increase in the number of typhoons, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires. Credit: Tom Cooper (via Getty Images)

Continued climate shocks over the last 15 years have resulted in an increase in economic migration among specialized laborers: in the US, skilled workers move from Midwest and North-Central states to other regions in search for economic opportunities. Similar migration patterns transpire in coastal nations in the Global South. By 2034, those living in rural areas in the US average more than two-hour drives for a general practitioner visit. In the Global South, this average increases to four hours as many hospitals are abandoned due to scarcities in key supplies, such as water, hand sanitizers, face masks, and other essential equipment.

The increasing intensity and frequency of climate disasters have forced the US government and private sector actors to invest in the green economy. The US green economy is booming, with 250,000 jobs created month after month in 2031. Profits have continued to multiply for manufacturing companies and those at the top, with the S&P and Dow Jones industrial averages reaching record highs, particularly for prices of futures on natural resources. However, work force insecurity has also continued to increase. Greater automation, coupled with volatility in the markets (the largest ever recorded across specific commodities), has led to an unequal distribution of jobs. In economic terms, the fierce race to restore planetary health has not benefited everyone.

The year 2030 commenced with the US-China climate competition (and, in some areas, cooperation) drawing comparisons to the US-Soviet space race of the 20th century. The scientific journal Nature Climate Change speaks of the “21st Century Climate Recovery Race.” Worldwide, investments in weather modification technology, food security and digital health continue to perform well. In 2022, US venture capitalists’ 1 trillion USD investments in the so-called Fresh Start initiative to support the Green New Deal has demonstrated promising results. Meanwhile, some parts of the world – first and foremost, Southeast Asian countries – feel left behind by Western governments as the latter focus on their own populations and seem to abandon the principle that “we are all in this together” when it comes to climate change.

The increasing intensity and frequency of climate disasters have forced the US government and private-sector actors to invest in the green economy. Credit: Science in HD (via Unsplash)

In 2028, after years of suffering from devastating climate events with meager assistance from Western governments, a number of Southeast Asian states (Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, etc.) come together in a show of unity and jointly commit to a goal of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Several climate catastrophes between 2024 and 2027 have shocked people around the world. Unseasonal winds and rainstorms across Europe have reached up to 200 km/h; the Marshall Islands and the Maldives have submerged; severe and prolonged droughts in the Middle East and other volatile regions like the Horn of Africa have fueled regional destabilization and conflict. By 2026, countries across the world are waking up to the undeniable reality that climate change is real and here to stay. Governments shift their resources to improve climate shock resilience, and worldwide investments in natural resources soar, resulting in unprecedented profits on futures like timber, which increases 150-fold.

By 2026, countries across the world are waking up to the undeniable reality that climate change is real and here to stay.

Concerns over the US’ faltering commitment to the Paris Agreement, coupled with ongoing climate disasters across the globe, have resulted in a scramble for critical natural resources and ensued in higher tariffs and protectionism during the last quarter of 2026. Related job losses have affected working classes worldwide. Sensing an opportunity, the Chinese government has stepped up, promising to lead global efforts in climate change mitigation and to prioritize environmental friendliness (and jobs creation) as part of its Belt and Road Initiative at the 2027 Shanghai Conference. In response, US state governors and tech leaders have vowed to continue the Green New Deal, which benefits both Americans and fellow world citizens.

Several climate catastrophes between 2024 and 2027 have shocked people around the world and further fueld destablization and conflict. Credit: zakir hossain chowdhury / Barcroft Media (via Getty Images)

The 2024 US elections see US Ambassador and Republican candidate Nimrata Nikki Haley elected as US president. Fearing that the climate critics would undermine the Fresh Start initiative and the progress made on the Green New Deal, Democrats redoubled their efforts to secure the House of Representatives but ended up losing the Senate. Over the next four years, Republicans and Donald Trump supporters relentlessly attack the Paris Agreement. The possibility of a US exit from the agreement and the influence of Donald Trump continue to cast a shadow over domestic and international politics.

In 2022, motivated by considerations of their social relevance, legacy, family, and philanthropy, venture capitalists have invested heavily in green and renewable energy. Encouraged by the Biden administration’s efforts to lead the fight against climate-related security challenges, venture capitalists and groups in the US and around the world (for example, Tim Draper, Guggenheim Partners and others) have invested almost 1 trillion USD in the Fresh Start initiative, thus supporting the Green New Deal. Moreover, a number of US states and corporations have entered into public-private partnerships to transform heavily coal-reliant states (Kentucky, Montana, Ohio, and Texas) into green energy hubs. This move generated a lot of discussions ahead of the 2024 US elections.

Deus Ex Machina

In 2035, a number of breakthrough technologies have become available to the public. This is the result of a period of growing private-public cooperation that began in 2022 and saw unprecedented levels of investment from both the public and private sectors. However, not all technology is accessible to the masses yet. While innovations drive positive developments (e.g., 3-D printed foods or the availability of GM seeds that require much less water), the deployment of technology is not always effective and, in some cases, the potential for conflict over access to water is even exacerbated. Farmers increasingly refuse to purchase efficient GM seeds (based on unsubstantiated health concerns and dis- or misinformation), leading to food shortages worldwide.

By 2034, new food technologies, such as vertical farming, are available but difficult to scale. Hailed as the future of the meat market, 3-D printed foods see an unprecedented level of investment, with $25 billion earmarked for the start of 2035 alone. However, 3-D food technology is only available to the wealthiest. Food insecurity remains a reality for millions worldwide, as technological solutions are not equitably shared globally.

As resource scarcity, land grabbing and the depletion of drinkable water intensify, the early 2030s see food and tech companies mainstreaming scalable technologies, including GM seeds. At the same time, dis- and misinformation on GM foods swamp social media worldwide and are further fueled by nations interested in destabilizing their regional competitors. Media illiteracy, frustration with economic inequality, climate fatigue, and social insecurities have propelled a burgeoning “anti-genetics” online movement, which disrupts major crop sales. In February 2031, Indian farmers from Punjab and Haryana burn GM crops from Bayer on the steps of the Indian parliament, despite early warning signals of a coming famine in Gujarat. Despite these upsets, investments in AgTech, which is seen as the “only way forward,” continue to rise.

Media illiteracy, frustration with economic inequality, climate fatigue, and social insecurities have propelled a burgeoning anti-genetics online movement, which disrupts major crop sales. Credit: Sion Touhig (via Getty Images)

Concerns over access to drinking water top the political agenda for many governments, particularly those in drought-prone areas. From 2025 to 2033, a US-Israeli private consortium joins forces to develop state-of-the-art weather modification tools to enable precipitation and safeguard Israeli food supply against “stolen rain” from the 2026 “Verdant Desert Initiative” that Israel’s neighbors introduced. By 2033, in a demonstration of state power, Geshem LLC launches in Tel Aviv. The company promises rain “on demand” for both nation states and Big Agriculture. The same year, climate and agriculture mitigation technologies provoke new controversies and receive record funding.

In 2030, Tesla has successfully implemented renewable energy networks in Texas, New York, Montana, and Wyoming. Meanwhile, the Chinese firm Evergrande has released a new fleet of electric cars that appear oddly similar to Tesla’s vehicles and has established a grid network in Shanghai. The rise in tech solutions for water scarcity issues (e.g., by Geshem LLC or through the Verdant Initiative) coincides with an expansion in green energy networks.

By 2029, investment in water futures have soared as news broke worldwide that underground water sources and aquifers would not sustain the 9.8 billion global population projected through 2050. Speculators are betting on the high price of California water futures and seize their outsized positions to control the market. Daily trade volumes reach a 100 percent increase from the same period in the previous year. In late 2029, Robinhood (a trading website popular on Reddit) halts all water futures trading, fearing speculation due to increasing investment in geo-engineering and weather modification technologies as well as ongoing water scarcity.

In 2029, investment in water futures have soared as news broke worldwide that underground water sources and aquifers would not sustain the global population projected through 2050. Credit: Muratart (via Shutterstock)

The years 2026 and 2027 have witnessed severe and prolonged droughts in the Middle East and other volatile regions. To avoid another Syrian War, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates launch the “Verdant Desert Initiative” to expand investments in sustainable farming in the Middle East to nearly 1 trillion USD over five years, and to increase arable land through weather (precipitation) control techniques. While the underlying science has proven unreliable, tensions in the region escalate: although attribution for changes in rainfall patterns proves scientifically fraught, Israel’s right-wing government still blames the Verdant Initiative’s actions for shifts in the country’s rainfall patterns.

By 2026, global wildfires are becoming increasingly frequent. However, the year will mainly be remembered for the worldwide explosion in illegal logging, which sees an increase of over 200 percent that, in turn, results in timber futures skyrocketing by 1,000 percent. Financial systems are undertaking serious efforts to adapt to climate-related pressure. Over the next few years, micro-level climate insurances, like wildfire house insurance, become widely available. Nonetheless, the possibility of a global climate-related financial crisis looms large.

The climate crisis had picked up additional speed a few years before. From 2022 to 2027, a number of climate disasters hastened the search for technological solutions for adaptation and mitigation strategies worldwide. In 2025, South Africa experienced an unprecedented fifth wildfire season, prompting the Cape Town Conference to discuss wildfire risk mitigation as fires raged simultaneously in Australia, India, parts of Europe, and Russia.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

By 2034, a number of coastal regions have flooded or sunk into the sea due to tropical storms, hurricanes and typhoons. Erratic monsoon rains have triggered unprecedented mudslides, burying tens of thousands of the most vulnerable people along different coastal areas. In Bangladesh, for example, thousands were left homeless, hungry and unaccounted for after a series of mudslides. Overwhelmed by the situation, the government in Dhaka demanded resettlement for the Rohingya in Myanmar, who had fled from persecution to Bangladesh in 2017. Other parts of the world began disappearing a few years earlier. After the Marshall Islands and the Maldives submerged in 2026, a series of hurricanes between 2027 and 2030 threatened the Caribbean. In 2028, a tropical system brewing north of Columbia quickly intensified, battering large parts of Jamaica, Anguilla, St. Maarten, Dominica, and the Lesser Antilles. Large sections of these islands were destroyed and their inhabitants killed. Over the course of these events, major global powers entrenched themselves in economic and technological competition, establishing alliances based on shared climate concerns.

In 2032, a special investigation by US and European intelligence agencies revealed that the Russian GRU (the country’s military intelligence agency) instigated the global online disinformation campaign against GM seeds, which resulted in global food shortages affecting the economically most vulnerable. Despite this revelation, farmers across Africa continued to refuse seeds sourced from Bayer for agrarian assistance, citing inconclusive health and safety issues, including claims that these seeds cause impotency.

In 2034, many coastal regions have flooded or sunk into the sea. Erratic monsoon rains have triggered unprecedented mudslides, burying tens of thousands of people in coastal areas. Credit: AJP (via Shutterstock)

Between 2030 and 2034, several economic and political developments culminate in the creation of international “Climate Clubs,” with countries collaborating on similar climate objectives and competing against the other clubs. In 2030, at the World Trade Organization (WTO), Tesla sues a Chinese conglomerate for corporate espionage, highlighting the sophisticated approach used to steal information from Tesla. A series of accusations and harsh exchanges between the US and Chinese governments follow, further entrenching competition between the two economic powers. Their respective allies strategically offer selective support. Other developments include the US and Japan cooperating on grid-bypassing systems, while China and the EU collaborate on 5G smart grids. The EU and China also enter into a bilateral treaty on climate refugees, while the US establishes a different climate refugee status as well as a global tribunal system for global ecocide. In addition, both the EU and the US implement a carbon border tax, thus alienating developing countries that lack climate ambitions.

By 2029, more countries have aligned themselves with either the US, China or third-party blocs. Regional alliances result in a securitization of newfound investment opportunities. Meanwhile, corporate espionage becomes ever more sophisticated, costing the global economy more than 5 billion USD annually and provoking deep mistrust between regional innovation hubs.

In 2028, after a series of climate disasters and abandonment from Western governments, capital cities across Southeast Asia voice their frustration with global climate governance. China announces that it will share geoengineering and weather modification technologies with its Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) neighbors and set up a climate relief fund for Southeast Asian countries. Further, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson alludes to Beijing’s consideration of revoking patent rights for weather modification technology to facilitate access for middle- and low-income countries.

In 2028, China announces that it will share geoengineering and weather modification technologies with its Southeast Asian neighbors and set up a climate relief fund for Southeast Asian countries. Credit: Mont592 (via Shutterstock)

From 2024 to 2027, catastrophic climate events have wreaked havoc worldwide. By 2027, the US-China competition in the climate race has advanced significantly, with the US focusing on the climate change-related impacts on its own economy and other domestic issues. Anticipating an opportunity to further assert its power, the Chinese government appoints itself to lead the global charge in climate change mitigation at the 2027 Shanghai Conference.

In 2023, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU is increasingly fractured and populist politicians face encouraging election prospects (such as Marine Le Pen in France in 2022). The US is concerned with domestic politics and social justice issues (including economic inequality, racial and gender equality, infrastructure, and public health), withdraws its troops from the “Forever War” in Afghanistan, and is actively grappling with China. In the post-Brexit world – and without a unified voice – the EU is repositioning itself and increasingly struggling to assert its place in global politics. China seizes the opportunity to intercede and enhance China-EU cooperation, including on 5G technology, smart grids and renewable energy that will increase jobs on the continent.

In 2022, following political developments and venture capitalist investments in the US and other countries worldwide, HSBC, BNP Paribas, Goldman Sachs, and other large international banks convene to agree on mandatory social costs on carbon, as well as metrics for valuations, discount rates and loan terms. Concerned with their personal legacy and credibility issues, extremely wealthy investors lead a push to update the Corporate Climate Social Responsibilities (CCSR) agenda for their investment banks.

In 2023, the EU is increasingly fractured and populist politicians face encouraging election prospects, such as Marine Le Pen in France in 2022. Credit: Frederic Legrand (via Shutterstock)

What Are the Main Implications of this Scenario?

Having explored the possible futures of Scenario I, the working group considered the most important implications and reflected on the following questions: How could the worst outcomes of the scenario be avoided and some of the worst consequences be mitigated? Who are the actors that can take action? And which steps should they take?

All Politics Are Local

Implication: Local political developments will influence domestic politics, which will significantly shape national political decision-making and determine how countries position themselves at the global level. The manner in which political mobilization manifests at the domestic level will create unique internal pressures. Government responses to increased tensions, conflicts and political mobilization locally and domestically will vary, depending on the nature and style of governance. The consequences flowing from that as well as subsequent state/government responses will differ.

No Deus Ex Machina

Implication: Technology will only be part of the solution. Questions regarding access to technology and its scalability, costs and effective deployment as well as sustainability will foment pressures within and between countries. This indicates that technology needs strategic consideration as part of a broader strategy to counter the negative impacts of climate change. Tax incentives could play a considerable role in spurring innovation. Climate change affects everyone. A more equitable distribution of geoengineering and weather modification technology will save lives and reduce unnecessary suffering for millions around the world. This includes facilitating knowledge and technology transfer as well as a wide-scale availability of intellectual property.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

Implications: Private enterprises will amass further power and influence in shaping world events and both the local and global level. Corporate competition and collaboration will become increasingly symbiotic with the states that headquarter those industries. Governments will need to incentivize corporations to “pay their fair share” and to distribute scalable technologies effectively and rapidly through increased coordination.

One implication of this scenario: private enterprises will amass further power and influence in shaping world events at both the local and global level. Credit: Matthew Henry (via Unsplash)

Mitigating Adverse Effects: Who Can Do What?

All Politics Are Local

Social media platforms and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should mobilize local resources, assets, logistical expertise, and networks to support domestic policies that aim to counter the consequences of climate change.

No Deus Ex Machina

To reduce the potential of international conflict, the G20 should negotiate tax and export control agreements, including with support from corporations and academia on intellectual property topics (i.e., copyrights, trademarks and patents). Academic institutions and think tanks should provide proactive support and develop new ideas for ensuring equitable access to and a fairer distribution of geoengineering technologies between wealthier and less well-off countries. Governments should prioritize the education of their citizens and business shareholders on the scientific credibility of geo-technologies and invest in efforts to curb related, widespread misinformation.

Fractures and New Connections in a Multi-Polar World

Citizens (and consumers) should demand and incentivize corporations to adopt more climate-friendly business approaches. This can be accomplished through means like individual purchasing power, crowdfunding or “blended finance” (i.e., the use of capital from public or philanthropic sources to increase private sector investment in sustainable development). As corporate competition and collaboration becomes increasingly symbiotic with the states headquartering those industries, national governments should prioritize the promotion of innovation and business coordination. Public-private cooperation across borders can help to rebuild fractured alliances through economic integration, collaborative technological development and joint innovation research. To strengthen crucial public-private partnerships, governments worldwide should facilitate blended-finance approaches in their national planning strategies and support large-scale private sector projects of geopolitical relevance. While governments step up their involvement in private-sector activities through subsidies and investments, companies (and especially those in the FTSE100) should, in turn, make more socially responsible decisions. This includes promoting the concept of a social cost of carbon and factoring global inequality awareness into their calculations. Win-win agreements in negotiating public-private partnerships should require effective coordination and reflect public values and political objectives (such as combating climate change).

Snapshot of Scenario II

It is the year 2035 and climate change is considered the central challenge of the 21st century. A process of power redistribution from West to East is shaping the new global political landscape. Tensions between powerful countries (namely, the US and the EU on one side, and China and India on the other) are triggering occasional conflicts and promoting pluralist – instead of one unified – governance regimes. Overall, climate disruption is moderate due to a global acceleration of adaptation and mitigation measures adopted between 2022 and 2035 (specifically in the realms of renewable energy, afforestation, carbon capture and storage (CCS), value chain carbon footprint reduction, and circular economy). Nevertheless, global warming persists. As rising sea levels cause islands and coastal cities (such as Miami Dade County, Venice and Alexandria, to name a few) to disappear, an increasing number of people are evacuated or manage to retreat. Domestic migration is, for the most part, well organized. Those affected by climate disasters are usually relocated effectively. Undocumented international immigration, however, causes humanitarian emergencies to proliferate at the European and US borders, as government interventions strictly regulate and forcibly prevent cross-border migration, often through use of violence.

To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming.

Due to overall global population growth, the agricultural sector is under significant strain. Production has become increasingly exposed to climate shocks, leaving small and individual farmers particularly vulnerable. To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming. Technological advances are not only revolutionizing food production but also increasingly relied upon to combat climate change. Geo-engineering technology, such as CCS, is widely available to states and corporations. However, in some cases, it functions ineffectively, as the geological properties of the chosen storage sites are less promising than initial estimations had anticipated. States and markets are financially resilient and effective in their responses to climate shocks, which have mostly become predictable and manageable.

To meet the world’s growing food demands, technological breakthroughs enable farmers and farming companies to increase productivity through hyper-intensification and industrialized farming. Credit: Thomas Barwick (via Getty Images)

International cooperation has resulted in more effective and credible global governance regarding climate policies and climate-related conflicts, and it intensifies among countries within the same regional blocs. These alliances are formed based on their respective leading states’ political and economic power, which includes access to scarce natural resources, capital, military capabilities, and technological innovations. While these coalitions are not formed solely for the purpose of addressing climate issues, they evolve into alternate, pluralist governance regimes and provide a regional governance framework for climate change-related actions, including by facilitating access to climate technologies and investment capital and governing regional migration. These blocs negotiate on behalf of their members within larger geographical, economic and political alliances, usually led by powerful states (for example, China, India, Africa, Europe, and the US). Tensions between blocs are increasing due to competition over natural resources that are key to the global energy transition. Despite multilateral efforts to address this challenge, scarcities are becoming more severe, as the growth in consumption and production outstrips the availability of critical resources like rare-earth materials, fertile agricultural land and, in some parts of the world, water resources. Insufficient access to such resources drives the exploitation of deep-seabed minerals and the Arctic as well as support for space resource exploration (for example, on the moon and on Mars).

What Are the Main Factors Driving this Scenario?

A mix of climate, technological, political, and economic factors drives this scenario. While none of these drivers dictates the dynamic of our scenario, each one contributes to the future state of the world outlined above.

- Climate change is increasingly mainstreamed as a global and local agenda, as public and private sector actors reach a tipping point regarding investments in climate-friendly technologies (including, among others, renewable energy, sustainable transport and circular production methods).

- Climate change-related impacts are moderate (irregular climatic events, steady rise of temperature/sea level, etc.) and lead to some related migration.

- China and India emerge as leaders in international climate politics.

- Tensions emerge between blocs competing for scarce natural resources.

- Populations and economies continue to expand. While we foresee a continued decoupling of growth and resource use, some resource scarcities remain.

- Advanced economies with access to natural resources (such as China, India and the US) dominate the sphere of technological innovation.

Scenario II: Building the Great Green Wall

In 2035, the world achieves 100 percent clean and renewable electricity, continuing on a path toward decarbonizing the world’s economies. The 40th United Nations Climate Change Conference, which takes place that year, establishes new and legally binding obligations for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) parties to achieve the goal of a maximum of 1.5 degrees of global warming. While this long-standing international climate governance body still functions as a forum for multi-national dialogues, the implementation of climate change-related actions has become largely delegated to different regional blocs. Divestment from fossil fuels reaches a critical point: Exxon becomes bankrupt, while BP, Equinor, Shell, and other former extraction giants now thrive as players in the market for renewable energy. Carbon offsets reach 500 USD per ton globally. A year earlier, in 2034, a stringent global carbon tax regime has been introduced: companies that have not achieved carbon neutrality by 2035 will have to pay a 50 percent income tax. Many Pacific Island states descend into chaos due to the adverse effects of different climate shocks. Their inhabitants are either evacuated to neighboring mainlands or migrate to “safer” areas within their respective islands (like Fiji).

In 2035, the world achieves 100 percent clean and renewable electricity, continuing on a path toward decarbonizing the world’s economies. Credit: Raimond Klavins (via Unsplash)

Meanwhile, the world’s population continues to grow – especially in parts of Asia and Africa – and reaches close to 8.9 billion people. As the global population expands, so does economic growth. In 2035, African economies drive 20 percent of global GDP growth. In 2032, food security has become a major issue as the demand for food increases globally. To meet this growing need, 70 percent of the world’s food is now produced in intensive farming factories near mega cities with large populations where substantial efficiency gains are being achieved. This hyper-intensification of industrialized food production increasingly strains natural resources. In 2031, the global water use footprint of the agricultural sector has already been reduced by 50 percent: still, food production increasingly depends on resource-intensive technologies, which are already in high demand due to the global energy transition that is underway. The development and deployment of battery-powered vehicles in the transport sector, for example, requires contested rare-earth materials, as well as copper, lithium and nickel.

In 2033, a Dutch-Chinese company has developed ships that run on batteries and can travel ten times faster than previous generations. Consequently, alternatives to long-distance flights will soon become commercially available. In addition, there is a shift toward green and ecological mobility in large cities, which changes the way urban populations move around. E-mobility dominates urban transport, with high-speed mass transit increasingly replacing individual modes of travel.

As 2032 approaches, climate change adaptation is increasingly mainstreamed due to the continuous effects of regular – albeit moderate – climate shocks. These include irregular climatic events as well as the steady rise in temperatures and, subsequently, sea levels. This mainstreaming effect is reflected in the upsurge in global climate investment, which reaches 5 trillion USD, while coastal cities and some islands have fully submerged, forcing their inhabitants to relocate. While international cooperation has achieved very effective results in some areas, cross-border migration is still considered a national security threat in Western countries and there is a lack of coordination on or international management of this issue. Nevertheless, cross-border migration cannot be completely prevented, which repeatedly results in humanitarian emergencies at different borders as well as sporadic, geopolitical conflicts. In parallel, countries begin forming regional alliances in response to region-specific needs and crises triggered by climate change. Some governments encourage or accept climate-driven movements of people within established bilateral and multilateral (but not global) quota systems.

There is a lack of international coordination on cross-border migration, which repeatedly results in humanitarian emergencies at different borders. Credit: CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP (via Getty Images)

Two years earlier, in 2030, South Africa introduced a national water pricing system. Many non-OECD countries are considering similar efforts, as pricing water is increasingly perceived as a crucial instrument for effectively managing and allocating water resources. Major upheavals are underway in the transportation sector as well: the last internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle is sold in Europe. In the automotive market, electric vehicles now dominate the sector, while long-distance hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are projected to become cost-competitive within the next couple of years. In 2029, so-called “Climate Tech” companies are valued to have the highest market capitalization worldwide. Climate Tech refers to a broad range of sectors jointly working toward de-carbonizing the global economy, with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions. In 2028, all countries pledge to spend at least 5 percent of their national budgets on increasing “green cover” (i.e., a range of strategies to integrate green, permeable and reflective surfaces into cities and towns). By 2027, circular production methods and modes have become standard across sectors, leading to higher efficiency and the partial addressing of certain resource scarcities.

In 2029, so-called “Climate Tech” companies are valued to have the highest market capitalization worldwide. Climate Tech refers to a broad range of sectors jointly working toward de-carbonizing the global economy, with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions.

A year earlier, in 2026, India launched a 1 trillion USD global climate fund to finance investments in electro-mobility, hydrogen and public transport, as well as more productive farming. The Indian ‘climate package’ was inspired by the Chinese 1 trillion USD global climate fund, which was launched in 2022 and focuses on the clean energy transition, space exploration and climate resilience. In 2024, China launched the Asia-Pacific Alliance Against Climate Change initiative. China and India subsequently emerged as leaders in international climate politics, thus triggering competition with longtime economic front runners, such as the US and Europe. These vying powers begun forming blocs of alliances in economic activities and climate policies. That same year, Europe and the US implemented a global carbon tax regime that fueled geopolitical conflict between regional blocs, as China and several emerging economies promised to retaliate against this measure. International cooperation has intensified among countries within different blocs, while tensions between blocs rise. A handful of technologically advanced countries with greater resources (such as China, India and the US) now dominate the innovation sector. They leverage their technologies to form regional blocs and only permit access to their respective allies. In 2026, tensions rose between OECD countries and natural resource supplier countries, mainly in Africa and Latin America, over supplies of crucial battery materials (for example, lithium, cobalt ore and manganese), as these resources become increasingly coveted.

Major upheavals are underway in the transportation sector: the last internal combustion engine vehicle is sold in Europe. In the automotive market, electric vehicles now dominate the sector. Credit: THINK A (via Shutterstock)

As demand for these materials increases, new extraction frontiers are explored. This includes different seabeds, the Arctic and, most promisingly, outer space. The first initiatives are driven by the private sector, as Tesla joins forces with Indian company Antariksh to register plots on the moon in 2027. This move rattles European and US governments, which are witnessing the private sector’s progress in space exploration with growing concern and are themselves scouting greater space commercialization. The US, Europe, Russia, China, and India appear to reach consensus on a system to formalize mining and farming rights in outer space. At the same time, the African Union contemplates plans to establish its own space agency in the following year.

What Are the Main Implications of this Scenario?

Our scenario triggers certain questions regarding the main implications that follow from it for the possible global future(s) of climate-related conflict. Given the dynamics and constraints presented above, how can we achieve better outcomes? Who can take action? And what should these key actors do? How can climate-related conflict be mitigated or prevented?

To approach these questions, the fellows of this working group more closely investigated the possibility of regional blocs shaping the new multipolar world order laid out in this scenario.

China Bloc

For the so-called China Bloc, tensions in South China Sea decrease and resource issues are resolved amicably. The region invests heavily in new technological innovations in energy and transport to become the global leader in climate change technologies. Furthermore, China’s domestic resource management and energy problems are less likely to intensify, meaning that Beijing will be able to export innovative technologies to other countries – in the region and beyond.

South Asia Bloc

Greater cooperation between India, Bangladesh and Pakistan not only leads to agreements for sharing resources despite growing consumption, but it also increases overall stability and prosperity in the region.

Africa Bloc

The major participants of this group include Kenya, South Africa, Ghana, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Nigeria. Such a Pan-African coalition increases the possibilities of effectively engaging other blocs in the pursuit of shared interests on the world stage – through strategic alliances rather than individual states’ efforts. However, we do not foresee Africa to become a cohesive bloc like China/India and the US/Europe or to have any obvious center in its regional leadership. While each African country will optimize its national strategies, the African Union or alternative forms of regional alliance will emerge as a practical means to increase these states’ collective bargaining power against other major blocs, just as the OPEC formed loose ties to achieve stronger negotiation power in the global oil market. As populations and economies continue to boom, competition for scarce resources will also increase, permitting China and other bloc leaders to exert influence through economic, political and military support.

US/Europe

The United States and Europe remain key actors in the global climate governance arena, but they will be forced to provide concrete contributions in the realm of net zero-carbon technological innovation for worldwide impact. Both the US and Europe are increasingly reliant on cooperation with other blocs to pursue their individual interests, address trans-national challenges and safeguard global public goods.

Latin America

Latin American swing nations will have to strike a balance in positioning themselves between the West and the East. As primarily export-oriented economies, investing heavily in sustainable agriculture and mining will become paramount for these states to maintain their role as global suppliers of food and critical resources, such as lithium (Chile and Argentina). Protecting rainforests and other ecosystems is also vital for these countries to safeguard their climate resilience and economic strength, especially as accelerating deforestation and biodiversity loss between 2024 and 2030 systematically threaten their international position. This demonstrates that the bloc’s capability to steward biodiversity and forests must become an “insurance” against the risk of international intervention in the region’s public goods.

Middle East

Under the leadership of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the swing nations in the Middle East could occupy an interesting position in global politics by leveraging their oil resources until the world’s fossil fuel sources are depleted. While these countries rely on “oil money” for their economic prosperity, some of them will choose to invest their capital to become post-oil, carbon-free societies, including by promoting renewable energy and other actions on climate change. On the other hand, countries that fail to respond to climate change will see their economic prosperity wither over time.

Conclusion

How to reform existing global governance institutions so that they become more effective in negotiating the long-term approaches and interests of competing regional blocs remains a key question. Other vulnerable states that are excluded from these alliances are likely to form their own coalitions to maximize their political bargaining power against the major blocs. Multilateral organizations, such as the UN and other global fora, will need to reform and adapt to enact effective and efficient global governance, which will be increasingly important to mitigate climate change and establish adaptation measures commensurate with global warming levels – or at least prevent the most detrimental effects of extreme weather events and ecological disasters. Nevertheless, regional actors continue to assemble their own institutions (such as the Arctic Circle). This leads to the emergence of “parallel,” multilateral bodies that, on one hand, serve to address regional climate shocks and foster coordination on defense and security affairs.

On the other hand, these bodies increase the complexity of international politics, making global climate policy (even) more difficult. Regional bodies will face greater pressure to become effective institutions, compatible with increasing global interdependence on climate issues. Those organizations will also be relevant in other areas, such as security. Regional agreements on migration-related matters could address the movement of people driven from their homes due to both moderate (but sometimes extreme) climate-related shocks and economic reasons. As population growth continues, food production will also have to increase, which – given spiraling global inequalities, climate change impacts and escalating water scarcity – will likely require a certain level of technological innovation and creativity. Joint investments by states and sharing the rights to core technologies would be beneficial for advancing AgTech and Climate Tech globally. Proliferation of already-available technologies for climate mitigation and adaptation will also reduce the pressure on countries without access to such innovations. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, scaling up circular means of production and consumption, as well as further decoupling of growth and resource use can reduce tensions regarding resource access within as well as across blocs based on the assumption that less scarcity will result in less competition.

About the Methodology

When it comes to issues of global governance, what do we need to think about today in order to avoid surprises, mitigate risks, and make use of opportunities? In search of answers, the GGF 2035 fellows spent a year exploring three topics and jointly developing new and better ways of thinking about a future that they themselves will help shape.

To help them in this ambitious endeavor, the GGF method provided an intellectually challenging framework that enabled structured communication and rigorous thinking. The fellows used a tailor-made ‘scenario approach’ to construct plausible future trajectories for each of the three GGF 2035 topics and arrived at a better understanding of the challenges they have identified. Along the way, they challenged their own biases and perspectives, and combined their newly won insights with their individual convictions about the shape and role of global governance.

About the Fellows

Zach Beecher – USA, Director of Operations at Healthworx

Zach Beecher is the director of operations at Healthworx, the innovation and investment arm of CareFirst of Maryland, Inc. He also serves as a civil affairs officer in the US Army Reserves. Previously, Zach was the chief strategy officer of C5 Accelerate, the early stage venture arm and startup accelerator of the global technology investment firm C5. He has also served as the director of C5 Philanthropy, where he developed veterans training, counter corruption and counter trafficking programs designed to use tech as a tool for good. Before the private sector, Zach served with the 82nd Airborne Division of the US Army. A recipient of the Bronze Star, Zach deployed as the lead advisor for logistics in support of combat operations in Mosul, Iraq. He holds master’s degrees from the University of Cambridge and King’s College London as a Rotary Foundation Fellow studying strategy in both a foreign and domestic policy context. Zach graduated with a bachelor’s degree in public policy focusing on national security from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Sheila Carina – Indonesia, Analyst at Microsave Consulting

Sheila Carina is an analyst at Microsave Consulting, a sustainability consultant for Anwar Muhammad Foundation and board director at the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) in Indonesia. She is currently involved in the financial inclusion project, training of sustainability reporting for small medium enterprises in Indonesia and promoting quality engagement in Indonesia for the implementation of Agenda 2030. Previously, she worked as a training coordinator for Sustainable Development Goals for UCLG ASPAC and as an advisor for the inter-parliamentary cooperation at the Indonesian House of Representatives. In her 4.5 years of working experience, she has been involved in mainstreaming sustainable development goals and the promotion of sustainable thinking both at the local and national level. Sheila has also conducted environmental and social due diligence for small and large-scale businesses in Indonesia. She is a part of the Managing Global Governance (MGG) Alumni Network of the German Development Institute, where she had created a comic policy brief about the future climate cooperation with her team. Sheila holds a master’s degree in sustainability with a focus on business, environment and corporate responsibility from the University of Leeds and a bachelor’s degree in international business management from the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus.

Vivien Croes – France, Head of AOCS/GNC & Flight Dynamics, UK Department at Airbus

Vivien Croes is the head of AOCS/GNC and Flight Dynamics at Airbus in the United Kingdom and a reserve officer in the French Navy. At Airbus, Vivien leads several space electronics projects, managing the end-to-end product lifespan from bid management to development and production. Vivien also leads several improvement and deployment projects at Airbus, managing change in a mutating space sector. Vivien received a doctorate in plasma physics focusing on Safran aircraft engines, which ledto several publications in peer-reviewed journals. Vivien holds a master’s degree in business administration from the Collège des Ingénieurs in Paris and a master’s of science degree from the Ecole Polytechnique and the Technical University of Munich.

Tori Zheng Cui – China, Doctoral Candidate at Pennsylvania State University

Tori Zheng Cui is a doctoral student and research assistant with Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications at Pennsylvania State University. Her research interests focus on the influence of mass media on perceptions of scientific issues, with climate change as one of the specific topics. Prior to academic research, Tori worked with the Guardian and Caixin Media in China with a focus on public issues related to the environment, science, public health, and climate change. In 2014, she was selected as a Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT and has won several national and international awards for her environmental reporting. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from the Communication University of China and a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from the China University of Mining Technology.

Varun Hallikeri – India, Infrastructure Finance Specialist, The World Bank Group

Varun Hallikeri is an Infrastructure Finance Specialist at The World Bank Group. Over 10 years as a financial advisor, he has assisted private investors, governments, and multilateral institutions on energy and infrastructure policy and investments in emerging markets, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Motivated by his desire to address climate change and aid economic development, Varun specializes in facilitating renewable energy investments including through public-private partnerships. He previously worked as a management consultant at the Boston Consulting Group in Mumbai and as a legal advisor at Clifford Chance LLP in London. In his pro bono work, he has provided recommendations on legislative bills, assisted in legislative drafting, and testified before India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the National Law School of India University and a master’s degree from the Fletcher School at Tufts University.

Tomonobu Kumahira – Japan, Corporate Finance Director at Komaza

Tomonobu Kumahira serves as Corporate Finance Director at Komaza, a Kenya-based social enterprise running sustainable forestry programs for smallholder farmers in Africa. Tomonobu leads the concept development of the Smallholder Forestry Vehicle, the world's first financial instrument focused on smallholder forestry, which won the Climate Policy Initiative's Innovative Finance Award and launched Komaza's Corporate Finance team to accelerate sustainable forestry through finance. Formerly a private equity investment professional at Mitsubishi Corporation, Tomonobu has extensive experience in corporate finance, private equity and alternative asset fund development. Tomonobu also worked with Ashoka Social Financial Service, FAO and Cabinet Office of Japan to promote finance as a means to achieve socio-environmental impact. He holds a bachelor’s degree in international relations from Brown University.

Kathrin Ludwig – Germany, Project Manager at adelphi

Kathrin Ludwig is a project manager at adelphi, where she focuses in the areas of climate change adaptation, NDC implementation and global biodiversity governance. She develops tools and strategies for climate adaptation and the sustainable use of biodiversity. Prior to joining adelphi, Kathrin worked as an advisor for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in Mexico, where she supported the Mexican Ministry of the Environment (SEMARNAT) in planning the implementation of national climate policy and the development of innovative digital tools for climate protection. In the Netherlands, she advised Dutch ministries on new approaches to international biodiversity policy for PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Kathrin Ludwig holds two master’s degrees in global environmental governance and social research from Vrije University Amsterdam. She is also certified in climate adaptation finance from Frankfurt School of Finance.

Michelle Toxopeüs – South Africa, Legal Researcher at the Helen Suzman Foundation

Michelle Toxopeüs is a legal researcher at the Helen Suzman Foundation, a non-governmental organization that seeks to promote constitutional democracy in South Africa. She is involved in supporting the strategic direction of the Foundation’s public interest litigation through targeted research and policy analysis. Michelle is currently leading a research project on water management in South Africa, with a particular focus on the role of governance in managing climate-related impacts on water security. Before joining the Helen Suzman Foundation, Michelle served as a legal researcher to Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke and Acting Justice Cagney Musi of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. With an interest in environmental justice, she holds a master’s degree in environmental law and governance from the North West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa.

Natalie Unterstell – Brazil, Director of Talanoa

Natalie Unterstell serves as director of Talanoa think tank and as a member of the Climate Finance for Latin America and Caribbean Group (GFLAC). Previously, Natalie worked as director of sustainable development fort the Presidency of Brazil, where she led the ambitious Brazil 2040 Climate Adaptation Program from 2013 to 2015, which aimed at climate-proofing critical sectors of the country's economy. Prior to that, she was the head of the climate and forests unit at the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment and served as Brazil’s lead negotiator at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. She is also a member of Agora!, RAPS and RenovaBR, civic movements dedicated to thought leadership and enhancement of democracy in Brazil. She is a frequent writer, media commentator and speaker. Natalie has a master’s degree in public administration from Harvard University, and a bachelor’s degree in business administration from Fundacao Getulio Vargas (FGV).

Senior Fellow

Thomas Hale – Associate Professor, University of Oxford

Thomas Hale is Associate Professor of Global Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. His research explores how we can manage transnational problems effectively and fairly. He seeks to explain how political institutions evolve--or not--to face the challenges raised by globalization and interdependence, with a particular emphasis on environmental and economic issues. He holds a PhD in Politics from Princeton University, a masters degree in Global Politics from the London School of Economics, and an AB in public policy from Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School. A US national, Hale has studied and worked in Argentina, China, and Europe. His books include Beyond Gridlock (Polity 2017), Between Interests and Law: The Politics of Transnational Commercial Disputes (Cambridge 2015), Transnational Climate Change Governance (Cambridge 2014), and Gridlock: Why Global Cooperation Is Failing when We Need It Most (Polity 2013). Thomas Hale is a GGF 2020 alum.

Acknowledgments

This report was co-authored with Joel Sandhu and Coco Aglibut of GPPi.

The Global Governance Futures (GGF) program is made possible by a broad array of dedicated supporters. The program was initiated by GPPi, along with the Robert Bosch Stiftung. The program consortium is composed of academic institutions, foundations and think tanks from across the nine participating countries. The core responsibility for the design and implementation of the program lies with the GGF program team at GPPi. In addition, GGF relies on the advice and guidance of the GGF steering committee, made up of senior policymakers and academics. The program is generously supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung.

The Global Governance Futures program (GGF 2035) off-sets participants’ carbon emissions related to carrying out and attending the program.